Hollow House Syndrome

brent simpson,

Hollow House Syndrome is a descriptive term that encompasses the dark side of what real estate professionals breathlessly promote as "Holiday Homes". It began in Switzerland in the 1970s, when urban Swiss discovered they could purchase beautiful ancient homes in small Swiss mountain villages for very low prices, perhaps as low as a month's pay or their company's annual bonus. During prime time - summer when the mountain flowers were in bloom, or around Christmas for the archetypal snow holiday, they would live in their new home. The rest of the year they would lock it up and let it sit empty. The Swiss have attempted to use legislation to curb the problem.

When Peter Mayle wrote his book "A Year in Provence", thousands of chilly Brits followed his lead and bought second homes in the French countryside... using it for about four weeks in August and then locking it up for the other 11 months. As more and more were converted, the local shops and bistros closed because their year-round buyers moved away. Eventually the only locals left were repairmen, maintenance and security people looking after the hollow homes. Locals were all too willing to cash in, selling their homes for twice, thrice or even ten times the price their neighbours could pay. The difference between what a London banker earns and a family farmer or the operator of a bistro in a local French village created a dual market. Whole villages in France were conquered by British... the first conquest of love (as in "Dahling, I just love our little place in Provence, so quaint... you must come visit us). People whose families had inhabited the village for hundreds and in some cases thousands of years were voluntarily displaced. Cultures died and nobody seems to notice.

It happened in the Algarve of Portugal, Cornwall and Devon in England, in much of Scotland. Indeed it seems to happen almost anywhere the land is cheap, the environment has something special and the natives both willing and not overly hostile.

Hollow house syndrome hit Waiheke Island in 2002. Where the average home on the island in 2000 was $200,000 (which requires a household income of about $50,000 to secure a mortgage - at a time when $50,000 was the average household income in Auckland), five years later the average home sale had jumped to $500,000. But the average household income in the 2006 census was about $60,000. What happened?

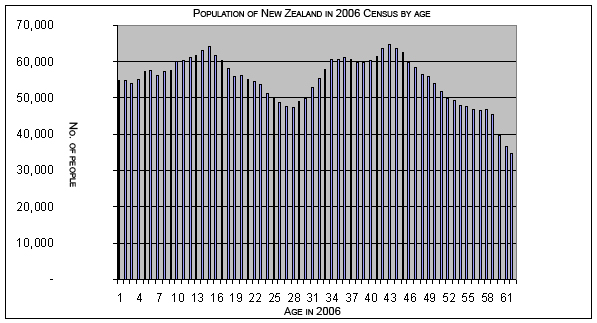

New Zealand has a camel hump demographic. It has a huge population in their peak earning and a very small population at the entry level. This peak earning group 40 to 60 has created a luxury market, and after buying the flash car, taking the overseas holidays and adorning with only the best brands, the next status purchase is the holiday home on Waiheke. Given that all have access to the same credit sources, prices rise until they match the purchasing power of this camel hump buyer.

Unlike the old baches of Waiheke, where the price was cheap because everyone in NZ earned about the same amount, hollow homes are expensive. Because they are expensive, and have fancy carpets and nice furniture, the owners have no desire or need to rent them out when they are not in residence. Tenants can't afford to pay a rent that comes near the mortgage, so the owners pull the white curtains, set the burglar alarm and call the security company. They leave it empty... hollow.

This benefits the territorial authority who taxes homes through universal rates. They get the money, but there is no one home to demand services. However, the local government act states the purpose of local government is “to promote the social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being of communities, in the present and for the future” and this is where the whole thing turns to custard.

Hollow homes destroy the economic, social and cultural well-being of communities.

People who live full time in a community become stakeholders. They have a stake in the well-being of their community and they volunteer their time, their skills, their love and their money to improve and uphold the well-being of their community. They are givers. In contrast, hollow home owners are, for the most part, not there. They may come to the local fund raiser held during prime time, and they may shop in the local stores when they are in residence, but when the local economy needs them the most – during off season, they are not there.

They are useless in civic organisations because they cannot come to meetings or volunteer if they are not in residence. They don’t volunteer for the Fire Brigade, the Red Cross or stand for service on the School Board. When someone gets hurt, or a child suffers a debilitating illness that burdens the family beyond what the state provides, they are not there to chip in. They love the cafés and restaurants filling them to capacity during prime season, crowding out the remaining locals. But during off-season the cafés struggle to survive and many fail because of the boom-bust nature fed by Hollow Home Syndrome.

From a social standpoint, their owners become leaches on the society. They arrive in prime time and expect to be welcomed by the locals – who being friendly folk for the most part, oblige. They are invited to parties where they tell of where they have been… always better places than “here” during the off-season. Because the part-timers represent the normal spectrum of society, locals become friends with them while they are in residence. But then they leave, and the social bonds that naturally form are cut until next year. Most people do not notice this effect, they simply accept it. However, eventually the social fabric of the society becomes weaker… bond-break, bond-break.

The community begins to lose its characters. The artists who were attracted by the beauty and the low prices can’t afford the rent. Those characters who bought in look at the current market price for their home and realise they can get ten times what they paid if they cash in and move to somewhere else that still is cheap. The solo mother who put on the dance classes for young girls moves away, the dance classes end. She also put on community shows, they end. Land that was available for cheap (or free) horse grazing gets bought up by millionaires who prefer to hire mowing companies. Gradually the pony club suffers and the serious riders move away.

The community built an intertribal, interracial marae back when community spirit was strong and the locals felt they needed a place to express mana whenua, given that tangata whenua had for the most part sold up in the early 1900’s. Strong leaders emerge, but then they leave. One deputy chair plainly saw he could not get a toe hold because housing prices were too high. Moved to the Cook Islands where his wife has ancestral lands. Another, an artist, shifted on – again because of the real estate pressure. Members supported on the benefit are somewhat protected, as the state provides adjustments for local cost of rent, but those seeking to stand on their own find the cost pressures simply too great. The biggest threat to the marae over the next decade or two is hollow house syndrome… that they will see their membership base erode because they can’t compete.

The economy becomes one of real estate sales, house builders, home maintenance companies, and others catering to the hollow home owners. The society gradually weakens as the glue that holds it together moves away. The culture loses its flavour as its people, those who hold and create the culture move to a more affordable place. The measurements of well-being show a decline.

In the end, it is a balance. Hollow home syndrome is toxic, but incrementally so. The more hollow homes, the more the community suffers.

There are two antidotes for hollow home syndrome – legislative and economic. Local governments can tax hollow homes higher, in effect putting a value on volunteerism. There are pony clubs in Auckland that have two membership rates. A low one for the traditional member who joins in the working bees to keep the club up, and a much higher one for the families who want to their child to ride, but not do any volunteer work. Many families are happy to pay, because they have the money, but not the time. The same model can be looked at by local government.

The economic model requires the community, and its planning professionals, make a concerted effort to create an economic environment that supports household incomes that can compete with hollow home buyers. If the average household income is $50,000, the average home price of $500,000 is unaffordable. But if the average household income can be increased to $120,000, balance is restored. In this latter case, there will be displacement. People with low incomes will be displaced by people with higher incomes, but the community will regain its strength as it gets full time stakeholding participants.

To earn $120,000 a year, one needs to be a professional or a successful entrepreneur. For such people to be attracted to a place like Waiheke, the economic conditions to make it possible need to be there… a place to work, high speed broadband, good schools, good transport, and a proactive calling. Of these, Waiheke lacks places to work and the schools are still struggling to get there. Both can be addressed.

In the absence of any such concerted effort, hollow house syndrome will respond to market forces. When credit tightens, the global economy retracts or the camel hump of demographics shifts from high demand to over-supply of homes, the prices will crash. Not drop, but crash because the purchase was discretionary and in part a symbol of status rather than an expression of need.