Church Bay

brent simpson, Erica Week, , Greg Treadwell

Church Bay, just south of Matiatia is fast growing into an exclusive retreat with its sprinkling of vineyards and olive groves including the renowned Mudbrick and Cable Bay Vineyards.

Church Bay Estate is said to have been the first subdivision of a farm in New Zealand, where the condition of subdivision was to plant half a million native trees to cause the native bush to once again rise. The rules were devised for Church Bay Estates, but applied to all of the western landscape from Park Point in the south to the northern tip of Matiatia Estates. The resulting bush is now over five metres in some places, and native species of birds becoming abundent.

For a long time, Church Bay remained a place of vacant sections and paddocks until the Cable Bay Vineyards came up with the idea of leasing land from landowners at a low annual fee and plant vineyards. Within a matter of years, the physical beauty of the area transformed and with it came a few character homes built at approximately the same time. Each of these homes reflected the dream of their owners, and the sum total of the vineyards and character homes turned Church Bay into a premier location. Long standing residents became amused as people began to refer to them as rich, although when the Council's property valuations began to agree, the amusement waned a bit. As the real estate values rose, some of those families who built the character homes began to sell as the capital values kept going up. Others are still holding on. At this time, one of the character homes, Te Rere, an American coastal shingle style mansion is slated to be torn down and replaced by a French Chateau style home.

Church Bay has several eco-homes, including Mudbrick Restaurant using a traditional mud brick, a private home on the Cable Bay property using a poured earth method, and a private home on Motukaha Road using the locally developed Ogletree-Elvy earth-brick method that uses crushed GAP-40 from the local quarry.

Church Bay headlands is the site of the Sculpture on the Gulf event, held every other year. As a result, the tramping trails in Church Bay are some of the best on the island, as they needed to be upgraded to handle tens of thousands of visitors during the sculpture event.

History[edit]

During Maori rule, Waiheke was unusual in that tribal rights to land and resources, and the Mana Whenua which accompanied it was shared among several iwi. Ngati Paoa migrated to Waiheke only in the 18th Century, Even on Te Huruhi, the last Ngati Paoa block, in 1896 census 58 residents were of six other iwi. This multi-tribal, multi-cultural pattern holds today in the Piritahi Marae in Blackpool, established in 1982 (established by the people of Waiheke County, including many Pakeha, who felt the island needed a marae for all races, provided a peppercorn lease and helped build the wharenui).

Never-the-less by the 19th century, in western Waiheke, Ngati Paoa was in full control. In the early part of the 19th Century, Ngati Paoa was in its golden era. Described by Major R. A. Cruise in his journal “In appearance these people were far superior to any of the New Zealanders we had hitherto seen – they were fairer, taller and more athletic, their canoes were larger and more richly carved and ornamented and their houses, larger and more ornamented with carvings than we had generally observed.”

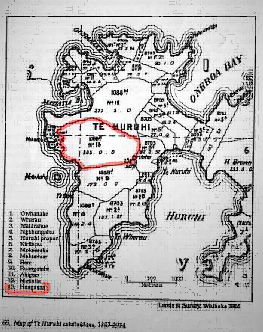

As the century progressed, intertribal war and land sales eroded Ngati Paoa stature, but throughout the 2,100 acres of Te Huruhi remained in tribal hands. In April 1869 the Land Court declared Te Huruhi a Native reserve with five Ngati Paoa trustees. By keeping communal title, this became the last block remaining in Ngati Paoa ownership.

The period from 1830 to 1890 saw Te Huruhi flourish. Several different families shared the common lands, but all traced their ancestry back to Te Toki, the son of Hura, thus the Hapu was called Ngati Hura of Ngati Paoa. The Hoete/Keepa, Rehutai and Karaka families were prominent, as were the two men given land by the Hapu, the former slave Ropata Te Roa who was given Matiatia and the whanau of Patena Puhata who was given Kiritapu (see Section No 6 in the survey map, below).

Three kainga (villages) stood on Te Huruhi, one at Matiatia, one in Blackpool, where the Piritahi Marae now stands, and one in Hangaura, now known as Church Bay Farm. For the most part, the housing in these kainga was weatherboard cabins and native raupo whare except at Hangaura where an exceptionally fine house stood on the land until it was sold in 1921 and moved to Matiatia. While the supreme chief of Ngati Paoa was a wily man by the name of Hori Pokai, in Te Huruhi, it appears the father and son Wiremu Hoete and Wiremu Hoete Keepa, respectively, carried the high mana. Both appear to be men who had the personal character and qualities to wear the responsibilities which come with being Rangatira and Kaumatua. Their memory remains strong in Hangaura.

Hangaura - Church Bay Farm[edit]

In addition to a beautiful home and the long-standing presence of a chapel and then a church, Hangaura was known for its exceptional agricultural production.

The families in residence grew, for commercial trade in Auckland, extensive wheat and Indian corn, kumara and potatoes, rock and water melons and extensive fruit trees, producing peaches, apples, figs, and at least one quince tree. We know this because the quince tree remains standing today. A visitor from Cornwall, in 2004, was asked to identify the tree, then in full fruit. He was astounded both to see a quince tree, but also, coincidentally had been visiting someone in another part of the country the week prior, who had proudly shown him his quince tree, speculating that it was probably the last ancient one left in New Zealand. The visitor chuckled with the news he would later deliver, that at least one more stood. Sadly, no one cans the fruit for jam anymore, instead they fall to the ground.

Along the flats of Church Bay equestrian pursuits emerged, where horses were raced from the 1860s onward. Families bred horses with some seriousness, securing Arabian stock to better the bloodlines. Horses have remained a part of Te Huruhi up to the present time, with considerable equestrian activities both in Church Bay and over the hill in Blackpool.

Above the tidal land, the flats of Church Bay contained high grade shingle, mined for the building of Auckland. Indeed the 19th Century marked a period of extraordinary environmental destruction of the area with the consent, and often participation of the Maori owners, as they sold off and stripped first the timber forests and then the very land itself.

As a place of activity, Hangaura seems to have waxed and waned. The golden period under the stewardship of brothers Wiremu Hoete and Rawiri Takurua and the family of Arama Karaka seems to draw to an end with the death of Wiremu Hoete Keepa in 1890.

In 1894, Wiremu Maehe Hoete and others applied to the Native Land Court to subdivide the Te Huruhi block into 13 sections. The lines drawn corresponded with the de-facto lines established by the various whanau. The sense of community, held strong by the bonds of aroha as maintained by Wiremu Hoete and his son Wiremu Hoete Keepa were broken by the grandson Wiremu Maehe Hoete. This was further aggravated by the perpetual question as to loyalty and commitment to the land, as those called tangata whenua (people of the land) in the records often gave different places as their home, and not all were buried on Waiheke .

By 1900 the buildings appear to have begun to deteriorate, and while farming continued, the sense of community in Hangaura appears to have gone. In 1903 Rawiri Puhata the man designed as heir to Wiremu Hoete Keepa’s mana was living in Kerepehi, having moved there in 1893. Wiremu Maehe Hoete, now a Reverend, gave his home as Parawai, Thames and Neho Keepa while still on Waiheke was living in Awaawaroa. The ravages of disease and illness took their toll, and Waiheke was still a long, and sometimes rough boat ride from Auckland. With the transformation of the land into larger fenced grazing lands, the kainga villages gave way to pastoral runs and Te Huruhi eventually became a sheep station. The woolsheds were kept up, but the church was allowed to fall into ruins and by 1920, even the magnificent home moved away.

With the advent of the new century, Ngati Paoa’s role in Te Huruhi faded. The Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron took out a lease on a seven acre block at Matiatia, where the wharf and car park are now located. In 1906 a lease was taken out by the Devonport Steam Ferry Company, whose director, Alexander Alison would become an important name in Te Huruhi history. By the end of 1907 Alison was leasing most of Hangaura as well as Matiatia and Owhanake Bay and his son, Fred, who had begun a career in boat building (as befits a ferry operator) shifted to sheep farming.

By 1911, the rules on sales of Maori land had become less restrictive, and the now subdivided Te Huruhi became a surveyor’s lunch ticket as family after family sought to cash in on land which was obviously not deemed their ancestral place, the place where their whenua (placenta) was buried in their whenua (land). In 1912 with an outbreak of smallpox, and the next year an outbreak of tuberculosis further broke the will of the remaining community. The sheep, horses, cattle and pigs did well, as the community gradually transformed into a farm. As land came up for sale, the primary purchaser was Fred and Anna Francis Alison and by the late 1920’s they owned 2,360 acres, in effect the whole of the Te Huruhi block all the way to Surfdale. All that was left in Maori title was the urupaa in Hangaura where the church had stood and a 9 acre block at the southern headland to Matiatia Harbour

In the middle of Church Bay Farm, now in its fifth Pakeha ownership, is a small section of land which remains owned by Ngati Paoa, tangata whenua. On that site stood the church of Church Bay.

The Church of Church Bay[edit]

The name Church Bay comes from the Maori Anglican Church erected on the two rood site by Ngati Paoa on the gently sloped rise of land now known as Church Bay Farm.

The first church was built in Church Bay in 1833, believed to be a raupo chapel, built by the Hapu in residence. It was in this year that Rev Henry Williams visited. Similar visits by Samuel Marsden in 1820 and later by Bishop Selwyn in 1842 mark acknowledgement by Anglican religious leaders of the devout nature of the Maori population of Te Huruhi. Curiously, some of this history is explained through intertribal warfare, which had its bloodiest period in this time.

Forty years earlier, in 1793, NgaPuhi, under Te Hotete (father of Hongi Heke), captured Ngati Paoa chiefs and children and took them to the Bay of Islands. Additional captives were taken by Hongi Hika in 1821, the year after Samuel Marsden’s visit. They were released in the early 1830’s, but in their time of captivity some of them, including Wiremu Hoete, had received mission schooling at Paihia. We believe this religious instruction and belief may have inspired the church’s construction upon Hoete’s return to Hangaura, and the subsequent visit by Henry Williams (the translator of the Treaty of Waitangi into Maori and brother of William Williams, the author of A Dictionary of the Maori Language). Wiremu Hoete became a deacon in the church and eventually an Anglican priest.

The hapu built the last church in 1881. Hoete’s son Wiremu Hoete Kepa collected the building funds. It was built of kauri timber, measuring approximately 12 feet by 19 feet. Rehutai Pio Karaka, the last Maori owner of Hangaura, and a respected sheep farmer, was the last lay reader in the Church.

Eventually it was blown down in a gale, and the timber burned in a grass fire. The site remains tapu because of the burial grounds which were by the church.

Pakeha Ownership[edit]

With the Alison purchase of Maori land, Ngati Paoa’s stewardship faded.

In 1911, the Croll Family moved to Matiatia to manage the Fred Alison’s now consolidated farm. John Croll had worked for the Alison family on Browns Island where he ran a thoroughbred horse farm and later became a ticket collector on Alison’s ferry. Fred Alison had suffered a back injury during his boat building days, thus he relied on the Croll family to do much of the heavy farm work. For half a century, the history of Te Huruhi and Hangaura, or Church Bay Farm, became the story of the Alison and Croll families. John Croll and his wife Mary moved to Matiatia bringing with them several children, including Don Croll, who developed a remarkable relationship with the land, fulfilling in some regards, the stewardship which previously was ascribed to tangata whenua. Some of these stories are oral, and permission will be required to record them.

Don’s first memory of Matiatia was sitting on top of a house being shifted on a boat from Auckland. Still standing as the Harbour Masters building, Alison floated it over to become the Matiatia homestead. It was already 40 years old in 1911.

Don went to school in Te Huruhi, now known as the Old Blackpool School, and on his first day at school found he found the school had 30 Maori children and he and his sister, Agnes, the only Pakeha. Thus, they soon learned Maori fluently, much to the annoyance of their parents when they would speak thus among their elders, who did not know what they were talking about.

Don became close friends with the brothers Tamati and Ngaeiho Kepa, sisters Bella and Ngaronga Araoma and a family named Werama, all of whom lived in a Maori Whare in Church Bay. On the south-western side of Church Bay (perhaps near the Quince Tree?) Croll mentions the home of Rehutai Karaka who owned both the woolshed and the fine house which was shifted to Matiatia Valley where Croll’s two sons later lived. Croll reports almost all these families left in 1916, moving to the Miranda District.

In 1923, work began on the Matiatia wharf and more people began to come to the island. Croll recited what has become a familiar lament “As the island became more populated, the peace and quietness seemed to disappear and the island started to lose some of its charm for me." Croll moved away in 1927, but at the Alison’s request moved back with his bride a few years later. In 1933 ferry service was upgraded with a steamboat known as the Duchess, operated by a company called Watkin Wallace which left Matiatia at 7 am and returned at 7 pm.

One story Don recorded is of note, and worthy of being repeated in full:

I am now going to relate something which my eldest son and I saw one day when we were mustering and I doubt very much if any other white person has seen this before or heard about it, as up to now I have not spoken about this to anybody and to my knowledge, neither has any other member of my family. I am not going to mention the locality of this sighting as I don’t want this interfered within any way. This day, as we were mustering sheep, my son happened to look down and see this strange formation on the beach. We’d had a terrific storm the night before and the sea had washed the beach clear of shingle exposing this complete Maori burial ground. It was a most remarkable sight. It measured about 30ft by 40ft in area and consisted of row on row of skeletons ranging from children to adults. These were laid out on tea-tree sticks which were absolutely uniform in size, approximately the size of wooden peg and about 5-6 ft long. On top of these were woven flax mats and both sticks and mats looked in perfect condition, although I guess if they’d been touched, they would have disintegrated. The skeletons were more or less imbedded in the sticks and mats. We looked at this some time in awe, but having much respect for the Maori tapu, we did not touch a thing. Next day we went back and the incoming tide had covered it all over and they were in peace once more…

In the 1960s the Alisons retired and sold the farm. The Southern part was first purchased by the Alexanders, and about a year later sold to Mark Week and his business partner.

Mark Week and his wife Istima had a choice of purchasing either the north farm (now Matiatia Estates) or the south farm (now everything south of the Ocean View Road, including Church Bay Estate and Park Point). Mark reported preferred the gentle slopes of Church Bay and a particular feeling engendered, which was absent in the northern farm, which was subsequently purchased and held by the Delamore family until it was sold to the Amtrust Pacific Ltd. owned by New York billionaire investor brothers Michael and George Karfunkel and developed as the Matiatia subdivision. Mark owned Church Bay Farm for 17 years until he sold it to Nettie and Nick Johnstone.

Mark was an unusual man, deeply associated with an organisation known as Subud. In the interview that collected the historical information cited herein, at one point he commented about the significance of Waiheke, and in particular Church Bay farm. He said that Waiheke is a very important place in the future of the world, that there is a “very high reason for its being here, and billions of people will be influenced from here.” He said no more on that subject but shifted to discussing the merits of combining sheep and cattle on farms.

Under the stewarship of Nick and Nettie Johnstone, Church Bay once again changed. Originally, the Johnstones purchased all of the farm from Matiatia to the southern tip of Park Point, but shortly after purchasing it, sold Park Point to the Tichner family who are subdividing and selling it as life-style lots. The Johnstones were farmers, but found that as a farm it was not proving sufficiently productive, so over time a subdivision plan evolved for it.

Until that time, subdivisions of farms into life-style sections required the sections be economic units, meaning they had to generate an income, be it a rural panel-beater or a life-styler who planted a few low-maintenance olive trees to meet (or more truthfully, beat) the rules. What Nick Johnstone and his landscape architect Dennis Scott devised was a new standard whereby subdivision would be possible if half a million native trees were planted on the parts of the land too steep to support reasonable agriculture or a safe building section. In one way, this would, over the next hundred years, bring the role of Pakeha in Church Bay full circle, as once again, the magnificent forests which were standing here when Captain Cook arrived will stand tall, only this time, protected by law and covenant.

The Return of Ngati Paoa to Hangaura[edit]

Saturday, 24 June 2006. Matariki. Tribunal finds for Hauraki Maori

Jun 24, 2006 – The Waitangi Tribunal has found that substantial restitution is due to Hauraki Maori over the loss of land which has lead to poverty and social dislocation. The Tribunal has released its report on 56 claims covering the southern part of Tikapa Moana, which includes the Hauraki Gulf and its islands, the Coromandel Peninsula and the lower Waihou and Piako Valleys. The first claims were lodged with the Tribunal in 1988. The Waitangi Tribunal says the Crown has acknowledged that Hauraki iwi lost large areas of land during the land confiscation of the 1860s with very little compensation. The report says they have been marginalised by the transfer of land and resources to others, which has caused alienation and frustration. The Waitangi Tribunal says Treaty principles of dealing with utmost good faith have been breached and substantial restitution is due.

25 June, Sunday – As part of the Matariki celebration on Waiheke, beginning at noon, elders and rangatira of Ngati Paoa walked on to the last remaining Maori title land on Hangaura, the square section, landlocked in the Church Bay Farm which once was the site of the church, and remains the urupa-. Accompanied by members of Piritahi Marae and other citizens of Waiheke, stories were told whilst waiting for the elders to arrive, and then a prayer service was held. All except the elders walked the perimeter of the land, bound on three sides by a fence, and more karakia was said, including Ngati Paoa’s Eugene Rawiri acknowledging and honouring the work of Waiheke’s long-standing kaumatua, Kato Kauwhata, Nga Puhi, from Nga Wha in Northland. This ceremony had the full support of the present owners of Church Bay Farm, and its farm manager attended and offered full cooperation with the Iwi.

Photo of the ceremony taken 25 June 2006 CML